History of the real 'accidental death of an anarchist'

“The real-life events recounted in the play were partly a response to the ‘Hot Autumn’ of working-class struggle of 1969. For example, on 15 October there was a demonstration of 50,000 workers, in Milan against the high cost of living. On 19 November a hugely successful 24-hour general strike took place to demand changes in government housing policy. Rents were high – often for appalling accommodation – while many flats were left unrented. Much of the explanation of this state of affairs was the government’s lack of interest: public house building had decreased from 40 percent of the housing market in the 1950’s to 6 percent in 1969. In the course of the strike a police officer was killed during disturbances in Milan, although the immediate explanation given at the time was that he had been killed by demonstrators – in reality it is more likely that his death was the result of a driving accident involving another police vehicle. On 28 November a law legalizing divorce was passed in Parliament, and on the same day a national demonstration of engineers saw 100,000 marching on Rome” (Behan 64).

“On 11 December a Labour Charter between the government and the unions was signed. As the historian Paul Ginsborg has argued:

It represented a significant victory for the trade unions and for the new militancy. Equal wage increases were to be granted to all, the 40-hour week was to be introduced in the course of the following three years, and special concessions were made to apprentices and worker-students. The trade unions also won the right to organize mass assemblies at the workplace. They were to be held within the working day and were to be paid for by the employers, up to a maximum of ten hours in each calendar year.

The following day a bomb exploded without warning in Milan at the National Agricultural Bank in Piazza Fontana, killing 16 people and wounding 90. The ‘strategy of tension’ had started and it marked the beginning of modern terrorism in Italy.

A few hours after the bombing senior police officers were telling the press that the bomb had originated from anarchist or far-left circles. At the same time police squads were rushing around Milan’s State University looking for anarchists to arrest – without any evidence yet available the police had already decided who was responsible.

Two anarchists whose names will always be associated with the Piazza Fontana bombing (although they were both innocent and any involvement in it) were arrested soon after the bombing. Pietro Valpreda, a ballet dancer, was arrested three days after the outrage and was immediately accused of being part of an anarchist conspiracy to organize a whole campaign of bombings. He was never convicted, yet he spent three years in jail and since his release no one else has ever been definitively convicted of the massacre. Nowadays the vast majority of Italians believe that the massacre was in fact perpetrated by neo-fascist groups who were encouraged and protected by the secret service, and one therefore presumes that there was also a degree of government collusion” (64-65).

“The thinking behind the strategy of tension, whether it be the neo-fascist groups who planted a whole series of bombs in those years or their accomplices and protectors within the secret services and the state machinery, was to halt the growth in the strength of the working class. The placing of bombs at random targets, generally with no warning, was bound to create severe tension within society. It was vital for these forces to create the impression that it was anarchists, communists, trade unionists and so on who were behind the bombs, just as they had unquestionably been behind numerous strikes and demonstrations in recent years.

This impression was to be created by the judicial system in particular and the state machinery in general, with the help of a compliant media. Once people had accepted that the left was to blame, and the bombs continued, they would demand a clampdown on the left. On the first anniversary of the Piazza Fontana bombing the Christian Democrat committee for the province of Milan passed a motion which called on the government to ensure ‘a modern, correct and well-managed use of the security forces’ in order ‘ to bring to an end the climate of disorder and violence which could undermine the credibility of democratic institutions.’ The leader of the right-wing Liberal Party, Giovanni Malagodi, went even further:

Milan is living through hours of disorder provoked by violent and seditious minorities who are creating obstructions and generating tension and fear. Milan’s schools are ‘picketed’ by extremists who are stopping classes from taking place. Leaflets are being distributed which openly defy the law, inciting violence and insulting democratic institutions. Small marches are continuously criss-crossing the city and it seems that the only goal is to paralyze public life even further. The authorities appear to be dormant during such a grave moment, while a climate of fear is spreading among public opinion. It is not possible that a serious and democratic city such as Milan can be left at the mercy of an irresponsible and subversive minority who are, in fact, not protesting against the government but against a free democratic system.

It was hoped that the overall situation which would be created would be one in which it was unclear who was specifically responsible, so in order to stop the chaos and the bombings the left had to be repressed in general” (65).

“In the climate of fear and revulsion created by the bombings it was assumed that it would be relatively easy for the state to justify the suspension of normal democratic procedures and the repression of the left – a political climate would hopefully be created in which the left would be marginalized electorally in any case. Apart from an immediate weakening on the left, the final objective was the creation of a political system akin to fascism, hence the involvement of neo-fascist groups and elements within the secret service, many of whom had fascist sympathies. The attempt to create a witch-hunt of the left was initially successful: in order to avoid any ‘guilt by association’ with those apparently responsible for the bombing, many unions signed national contracts the day after the explosion in Piazza Fontana.

All of this is far from being an outlandish conspiracy theory, however. A week before the Milan Christian Democrats and Giovanni Malagodi made the statements outlined above there had been an attempted coup in Rome led by Prince Junio Valerio Borghese, although the news did not emerge until four months later. Even though the attempt was rather farcical, it was part of a tradition among senior military leaders, as witnessed by far more serious preparations for a coup in 1964” (66).

“The essence of the strategy of tension is outlined by the character played by Fo in the play, The Maniac, while talking to a character who roughly embodies the ideas of the PCI, a journalist named Maria Feletti:

the main intention behind the massacre of innocent people in the bank bombing had been to bury the trade union struggles of the ‘Hot Autumn’ and to create a climate of tension so that the average citizen would be so disgusted and angry at the level of political violence and subversion that they would start calling for the intervention of a strong state!

Apart from the play’s overwhelming critical acclaim and popularity both in Italy and around the world, the immediate political success of Accidental Death of an Anarchist was the fact that it played a major role in exposing the thinking of those who were organizing the ‘strategy of tension’” (66).

“The second of the two anarchists, Giuseppe Pinelli, associated with the bombing was arrested before Valpreda: he was picked up a few hours after the explosion when he arrived at an anarchist centre during a police raid. He was a 41 year old railway worker, married with two daughters, and was to die just 72 hours later in the Milan police headquarters, where he was being held illegally” (66).

“A few basic facts suffice to raise doubts in any rational mind as to how he met his death. Pinelli ‘fell’ from a fourth floor window to the courtyard below. The room he was being questioned in was just 13 by 11 feet; and there were five experienced officers in the room when Pinelli ‘flew’ from the window (which opened inwards) with a ‘cat-like jump’. The first police explanation was that Pinelli had committed suicide by jumping; indeed police chief Marcello Guida (The Superintendent in the play) immediately stated on television that his suicidal ‘leap’ was also proof of his guilt. The newspaper Lotta Continua commented: ‘Similar suicides occurred in Italy during fascism’” (66-67).

“The lack of any injures to his hands – which would have been caused by the instinctive reaction of cushioning his impact – caused immediate disquiet. A lifeless body suggests an unconscious or dead body. A journalist in the courtyard looked up in the dark when he heard some noises and remembered thinking: ‘What the hell are they doing up there? Why are they throwing a big box out of the window?’” (67).

“The other hypothesis which began to be discussed was that Pinelli’s death was genuinely accidental and that the police were trying to cover up their own shortcomings, including intimidation, which lead to his death. As the months wore on many people began to believe that his death was the result of oppressive interrogation techniques, often used by the police, which had gone slightly wrong. This is a variation of the hypothesis that he was effectively murdered by the police, which again, is by far the majority view today” (67).

“As investigation began, one of the most worrying elements was that none of the police officers under suspicion was suspended, thus giving them the opportunity to tamper with evidence. The first investigation into Pinelli’s death by Judge Giovanni Caizzi concluded in late May with the ambiguous verdict that it had been ‘an accidental death’, thus giving Fo the title. A mood was growing through the country that a huge cover-up was in operation, even an ex-Prime Minister, Ferruccio Parri, was moved to comment at a public meeting: ‘The judiciary is insisting on creating a legal verdict which saves the police, because the police are the state. If the police crumble into pieces so does the state.’

However Judge Caizzi’s verdict was released on the first day of a week-long newspaper strike, so it was ‘old news’ by the time the presses started to roll again. And despite his verdict, this public prosecutor then strangely requested that the case be dismissed. Nevertheless, a second investigation was held by Judge Antonio Amati who reached a verdict of suicide in early July” (67).

“The newspaper Lotta Continua was the most prominent in a widespread press campaign which strongly boubted the police’s explanations and the judicial verdicts. On 20 April 1970 Luigi Calabresi, one of the policemen probably present when Pinelli left the police headquarters via the window, took out a lawsuit against the editor ‘for continuous slandering aggravated by attributing to him a specific deed.’ The reading of these events was that Lotta Continua had been deliberately provocative in order to force the issue out into the open. Yet Calabresi’s move was similarly seen as n attempt to muzzle the press” (67-68).

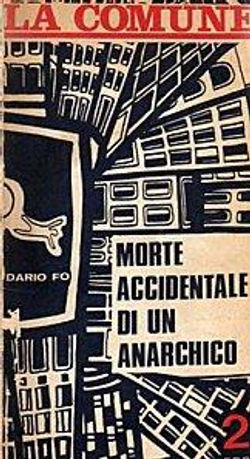

“The origin of the play illustrates Fo’s close relationship with this growing movement, as he explains: ‘During the spring of 1970 the comrades who were coming to see our shows – workers, students and progressives – were asking us to write a full-length piece on the Milan bombings and the murder of Pinelli, a piece which would discuss the political motives and consequences of these events.’

Sympathetic journalists and lawyers gave them background material and unpublished documents and a first draft was quickly completed. Fo then continues: ‘We were informed that we might be running the risk of legal proceedings, with trials and charges being brought against us. Nevertheless, we decided not only that it was worth the effort to try, but also that it was our duty as political militants. The important thing was to act and to act fast.’

When the libel trial against Lotta Continua opened on 9 October it was the first public hearing of the events surrounding Pinelli’s death. Fo later recalled that during the trial hearings, ‘The roles were completely reversed: Lotta Continua no longer played the role of the defence but became the prosecuting counsel against the police. All the policemen’s lies were uncovered, one officer contradicted another, they were hypocritical and fell into incredible traps.’

These hearings provided Fo with much of the dialogue for the play. The testimony of police officers was full of inconsistencies and ambiguities; at one point an officer was asked whether he had heard Calabresi utter a key phrase during Pinelli’s interrogation:

I’m not able to rectify or be precise about whether I heard that phrase because it was repeated, or because it was mentioned to me. As I believe I’ve already testified to having heard it, to having heard it directly; then, drawing things together, I don’t believe that I heard it. However I’m not in a position to exclude that it may have been mentioned to me” (68).

“In the script the instruction that he should often be rubbing his right hand refers to the suspicion that Calabresi had struck Pinelli violently. And The Inspector’s nervous tic also corresponds to a tic which observers noted in Calabresi during the libel trial. Anybody who had been following the trail closely and went to see the play would therefore have no difficulty in presuming that The Inspector was based on Calabresi. By the time he gave testimony, Calabresi’s normally confident and at times aggressive demeanor had changed:

Calabresi is no longer the prestigious person he once was, in front of the judges. Yes he’s still got his roll-neck sweater under a striped gangster suit, his sideburns are well groomed, but at tense moments an unstoppable tic makes him massage his firm jawline. He has lost his normal air of superiority (also because as soon as he appeared rhythmic chants began: ‘Mur-der-er! Mur-der-er!’)” (68-69).

“Fo’s play opened in early December, exactly a year after Pinelli’s death. Yet it was presented without any real publicity. A journalist who met Fo at the state university of Milan during its first week observed:

To look for information about Fo’s play outside of this building would be pointless. Here, everyone knew that Accidental Death of an Anarchist was being performed in Milan, and they knw the street name and the time. Normal channels of communication are blithely ignored, but even so yesterday evening at least 500 people had to go back home because the theatre couldn’t fit any more inside” (69).

“One of the fundamental political purposes of the play, therefore, was the need to draw general political conclusions from each individual scandal. At one point The Maniac outlines the normal sequence of events: ‘A huge scandal…A lot of right-wing politicians arrested…A trial or two…A lot of big fish compromised…Senators, members of parliament, colonels…The social democrats weeping.’

Yet The Journalist, who represents parliamentary socialism, thinks this would be a good thing…As parliamentary socialists want to gain control of the state machine, in the final analysis existing state institutions must be defended” (71).

“Accidental Death denounced the entire police force and the whole legal system, and made the point very strongly that the details of one particular scandal should be generalized to understand and illustrate the common patterns according to which the state normally works” (82).

Behan, Tom. Dario Fo Revolutionary Theatre. Pluto Press, 2000.

Why THIS play now?

Why this play now?

The topic of police and political corruption is not a new issue. There is a common phrase from 19th century British politician Lord Acton that comes to mind when dealing with this subject, "Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” This idea is fleshed out in Dario Fo’s political satirical farce Accidental Death of an Anarchist. Although the setting of the play is Milan Police HQ in 1970 the similarities to Hawaii’s current corruption investigations seem to resonate though this theatrical lens with unique self-awareness.

The play is based on and inspired by real events in Italy in 1969. One element that stands out as a direct parallel between the past and the present is how those involved remained in office. It was said that in Italy, “As investigation began, one of the most worrying elements was that none of the police officers under suspicion was suspended, thus giving them the opportunity to tamper with evidence” (Behan 67). Which is similar to the Kealoha case where Honolulu Police Chief Louis Kealoha and his wife Deputy Prosecutor Katherine Kealoha remained at work during the grand jury investigation and it wasn’t until the grand jury came back with indictments that Honolulu Police Chief Louis Kealoha was put on leave but his wife Deputy Prosecutor Katherine Kealoha has, as of today, remained active at her job.

Other parallels between the Kealoha indictment and Fo’s play include but aren’t limited to: tampering with evidence, tampering with witnesses, abuse of power and authority, conflicting testimonies, and attempting to frame a man of a crime he did not commit.

Although the Kealoha case will not be directly referenced during the play, anyone who comes to the performance will undoubtedly be able to draw parallels between the recent Honolulu Police issues and those that plagued the Italian Police in the 1970’s.

Research: Past & Present

Italy 1969-1979

Hawai'i / USA 2016 - 2018

We don’t have any products to show here right now.

Italians are still haunted by the Years of Lead

"On a bitter day in December 1969, a bomb exploded at a bank in Piazza Fontana, near Milan’s cathedral. Seventeen died. The young anarchist arrested in connection with the atrocity mysteriously died in custody. Three years later, the policeman accused of his murder was executed on the street. Things dragged on like this for years: six people were killed in December 1976 alone. All told, Italians suffered the nightmare of the “Anni di Piombo”—“The Years of Lead”—for 15 bewildering years. Hundreds died in the numerous attacks. The country’s films, books and music are still contemplating its significance.

The Years of Lead, so named for the number of bullets fired, emerged from the optimism of the economic miracle. While industrialisation..."

Incorrectly Targeting Leftwing Extremists

"On the evening of 12 December itself, the prefect of Milan, Libero Mazza, sent Christian Democrat prime minister Mariano Rumor, a telephone message that did not beat about the bush:

“Credible hypothesis that immediate inquiries should focus on anarchoid groups as well as extremist fringe. Following consultation with the judicial authorities, strenuous steps already underway to identify and arrest those responsible.”

The suggestion was plain. And it certainly would not find the officers in charge of the investigation all at sea. Inspector Dr. Luigi Calabresi, deputy head of Special Branch at the Milan Questura (police headquarters), was already targeting leftwing extremists. Motive? Look at the targets: banks and the war monument..."

Giuseppe Pinelli - the anarchist who 'fell'

"...in the aftermath of the December 1969 bombings he was arrested and taken to the central police station to be interrogated by Calabresi and his henchmen. On the evening of 15th December he "fell" from the fourth floor of the police station.

The state murder of Pinelli set off a wave of protest. One thousand people attended his funeral. Later Dario Fo wrote his play Accidental Death of An Anarchist about Pinelli’s murder and the framing of Valpreda...."

FBI investigating 4 Honolulu police officers for allegedly forcing suspect's mouth on public urinal

"The Honolulu Police Department then referred the case to the FBI.

'If true, these allegations violate the core value of what HPD stands form,' Ballard said. 'Our officers are sworn to uphold the rights of all persons and I expect every officer to treat every member of the public fairly and with respect. Personally I'm appalled.'..."

'No one is above the law': Former HPD chief, prosecutor wife indictedecond Item

"...former Police Chief Louis Kealoha and his deputy prosecutor wife stood before a federal judge Friday after being arrested and indicted in a public corruption probe that also netted the arrests of three current police officers and a retired major this week..."

Additional Articles

- click box for full article

Additional Articles

- click box for full article

Photographs from Italy 1969 - 1972

Click on each photograph to learn more.

|  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

|  |